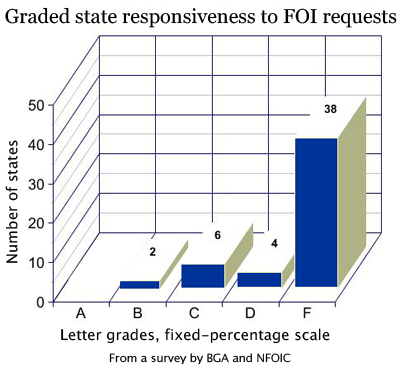

Better Government Association and National Freedom of Information Coalition give 38 out of 50 states "F" grade in overall responses to FOI requests.

- Analysis by the Better Government Association

- Overview by Charles N. Davis

Freedom of information laws are only as good as the response mechanisms built into the laws themselves. After all, if citizens can't take action to enforce their right of access shy of filing suit, what good are FOI laws?

When it comes to responsiveness measures, not much good at all.

The Better Government Association (BGA) and NFOIC have united to review the recourse afforded citizens in the public records laws of all 50 states, and the conclusions make for some relentlessly depressing reading.

The tools available to citizens to enforce their rights under state FOI laws are, with rare exceptions, endemically weak.

The haphazard construction of state public records laws has resulted in an information gap that significantly affects the citizenry's ability to examine even the most fundamental actions of government, the study found.

"This national study shows that in the vast majority of states, citizens have little to no recourse when faced with unlawful denial of access under their state's FOI laws," said Charles N. Davis, executive director of the National Freedom of Information Coalition, based at the University of Missouri School of Journalism. "It's a cry for reform of FOI laws nationwide."

BGA researchers, led by Executive Director Jay Stewart, studied all 50 state public records laws, and no state earned better than Nebraska's and New Jersey’s 14 out of a possible 16 total. (More explanation regarding methodology will follow.) A stunning 38 states earned F ratings, with the rest scattered between C and D. The results are dismal, the details depressing even to hardened FOI observers who knew the national situation was grim.

"The Freedom of Information Act is an incredibly important tool in helping citizens understand how their government works," said Stewart. "Just as states compete amongst each other to be the best in education, business environment and tax policy, the states should compete to be the best in responding to citizens' requests for public information, information they pay for with their tax dollars."

The BGA rankings were prompted by years of run-ins with obstinate public officials. BGA investigators have been refused requests to examine state contracts and performance measures, denied everything from documentation of ambulance response times to the documents reviewed when making budgeting decisions, and ignored by officials in nearly every major office at one time or another. NFOIC coalition members share similar tales of frustration.

So the BGA decided to find out where its home state of Illinois stood in relationship to other states. Could Illinois be an aberration in an otherwise sunshine-laden country? Well, the original BGA study showed that Illinois was no anomaly—in fact, Illinois was in the muddled middle of a dozen or so states that could be described as spectacularly average. Illinois is now one of the brighter spots, having improved somewhat since 2002, but the bad news is that few states improved at all, despite more attention to FOI thanks to the efforts of open government groups.

To build its ratings, the BGA created a "gold standard" against which the laws of each state could be objectively and accurately measured in five categories: Response Time, Appeals, Expedited Review, Attorney's Fees & Costs, and Sanctions. The total points each state received were divided by the total points possible, resulting in a fixed-percentage score. The percentage was converted into a letter grade: 90-100%, A; 80-89%, B; 70-79%, C; 60-69%, D; less than 60%, F.

The NFOIC jumped on board, offering to bring news of the rankings to its member coalitions and to use the rankings to focus attention on the need for FOI reform in many states across the country.

"Although several states posted respectable numbers in our survey of their Freedom of Information Acts, it is clear that most states still have a lot of work to do in making their governments more accessible and transparent," Jay Stewart said. "Even a low score of 66% puts a state in the top ten of the rankings."

Procedural Criteria

The study measured several criteria regarding access to information. The first three criteria that the BGA studied in assessing the strength of each state's open records act were procedural, involving the process the requesting party must undergo to gain access to public records.

Response Time

The BGA’s concern with these procedural requirements was that a lengthy and burdensome process would likely discourage citizens from making requests and seeking enforcement of the statute, which would result in less disclosure of public information. To assess the procedural obstacles facing FOI requesters, the BGA studied response times, the process of appealing FOI denials and expediency, and the means to give a case priority on a court's docket in front of other matters because of time concerns.

Although most states did well in this section of the survey, managing to respond within legal limits, few provide any sort of detailed, effective appeals processes. Citizens often have their requests denied and the only way they can gain access to records is by appealing the agency's denial. That’s where state FOI laws really begin to suffer.

Appeals

When citizens are able to appeal in a cost- and time-efficient manner, in the forum of their choice, they are more likely to challenge an agency's denial. The BGA's method of grading this criterion is based on three elements: choice, cost and time. A petitioner should be able to choose the body that hears the appeal. The appeals process also should provide for administrative remedies to control the costs and time of appealing.

States with statutes that do not provide for an appeals process do not receive any points. These states fail to inform citizens that the denial may be reviewed, and maybe reversed, by a higher authority. Allowing a petitioner to appeal a denial to court receives one point. Appealing directly to a court will assuredly be the most expensive and take the most time. Citizens are less likely to challenge a denial if an appeal means several years of litigation costing thousands of dollars.

A review of the rankings reveals that only 19 states had a full appeals process for FOI denials, while 31 states earned less than a full point — meaning that in the majority of states, a citizen has little or no recourse, save for the courts.

Two points were awarded to states that require petitioners to first appeal to the director of the agency denying them access, next appeal to an ombudsman and only then appeal to a court. By requiring a petitioner to exhaust both administrative remedies before allowing access to the court system, these states provide the petitioner no choice of forum. However, these states do provide for administrative remedies that may reduce the cost of the appeal if a favorable ruling can be achieved before going to court. By appealing first to the agency head and then to an ombudsman, there is at least a chance of getting a favorable decision in a cost- and time-efficient manner. The presence of a legislatively designated entity, either the head of the agency or an ombudsman—as an appellate avenue before resorting to the courts—earned states three points. States offering petitioners the choice of appealing to the head of an agency or an ombudsman, or going to court, received four points. Finally, states allowing citizens to pursue the channel of appeal of their choice received five points.

The results show that while many states’ public records laws allow citizens to pursue the appellate channel of their choice, some states force citizens to turn to the courts should they wish to appeal a records denial.

Expedited Review

Expediency means to give a case priority on a court's docket in front of other matters because of time concerns. The BGA examined each state statute to determine if a petitioner's appeal, in a court of law, would be expedited to the front of the docket so that it is heard immediately.

States that do not provide for expediency in their public record statute received no points. States requiring a case to be heard within 21-30 days after filing received three points. States received four points if they required a case to be heard within 11-20 days after filing. Finally, five points were awarded to states that require a case to be heard within 10 days.

Penalty Criteria

In the penalty category, the two criteria the BGA used to weigh the strength of each state's public records act focus on the penalties levied against an agency found to have violated the public records law.

The two penalty criteria are: 1) whether the court is required to award attorney's fees and court costs to the prevailing requestor; and 2) what sanctions, if any, the agency may be subject to for failing to comply with the law.

Attorney's Fees & Costs

The first penalty criterion the BGA used was whether petitioners were entitled to attorney fees and court costs in the event they prevailed in their action. Allowing for such an award serves two purposes. First, it assures petitioners that their expenses will be covered in the event they are successful in their appeal, encouraging people to challenge an agency's denial. Second, awarding fees and costs to the prevailing petitioner will provide a deterrent to agencies and promote compliance with the law.

Language is critical here; the BGA's grading scale for fees and costs contains phrases that warrant explanation. For example, "may" means that fees and costs are to be awarded at the judge's discretion, while "shall" means that fees and costs must be awarded to the prevailing petitioner. A statute that states fees and costs "shall" be awarded will be stronger than a statute that provides fees and costs "may" be awarded. There also is a major difference between "prevail" and "substantially prevail" in terms of recovering attorney fees. "Prevail" refers to a situation wherein the petitioner wins on all points, and is given access to all the records requested, while "substantially prevail" refers to a situation wherein the petitioner wins on only some points, loses on other points and is only given access to some of the requested records. States awarding fees and costs to petitioners that only substantially prevail will be stronger than those that require the petitioner to completely prevail in order to get fees and costs.

State statutes failing to provide that a prevailing petitioner could collect fees and costs received no points. Allowing recovery of fees and costs in the event the agency acted in bad faith in denying the record scored states one point. States allowing an award of attorney fees and costs at the judge's discretion when the petitioner prevails received two points. States receiving three points also leave awarding fees and costs to the discretion of the judge; however, the petitioner must only substantially prevail before a judge may consider the awarding of attorney fees and costs. Four points were given to states that require an award of fees and costs to a prevailing petitioner. Finally, states requiring an award to petitioners who only substantially prevail received five points because they provide the most protection to petitioners from the outset.

Sanctions

The final criterion the BGA examined in assessing the strength of each state's open record act was sanctions. The BGA looked to see whether there was a provision in the statute that levied penalties against an agency found by a court to be in violation of the statute. Without a sanctions provision, a public records statute means very little. It is only when an agency is punished for breaking the law that the law will be followed.

States that do not specifically punish an agency for non-compliance with the statute received no points. One point was awarded to states with statutes that provide for either criminal or civil sanctions in the event there is a violation of the law. The BGA gave two points for statutes that provided for both criminal and civil sanctions, and three points for states that provide for either criminal or civil sanctions and increase those sanctions for multiple offenses. States with statutes that provide for both criminal and civil sanctions and increase those sanctions for multiple offenses received four points. Finally, states that allowed for termination of an employee who violates the statute received five points.

What to do next

Take a look at the numbers for your state, and then for other states, and you'll come to one inescapable conclusion: state FOI laws are in desperate need of reform. From the moment a citizen walks into the state agency to make a records request to the final denial of access by a state court, each step in the process is, in most states, a stacked deck in favor of governmental secrecy. The BGA report might simply confirm what you already knew about FOI in your state, but it should serve as a catalyst for change.

What to do? Well, without trying to be too self-serving, might we suggest you look into joining (or at least contributing to) groups such as the Better Government Association <http://www.bettergov.org/> or the National Freedom of Information Coalition <http://www.nfoic.org/> or one of its local coalitions <http://www.nfoic.org/members>?

If that doesn't suit, perhaps you'll find other ways to do your part to help us ensure that our government not only works for us, but does so as openly as possible.

James Madison wrote that "[a] popular Government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or, perhaps, both."

We must strive to write our own history, replete with openness and freedom of information.

–October, 2007

———————

The Better Government Association applies investigative journalism techniques, litigation, and public policy studies to expose problems, inform citizens about the operations of their government and lay the groundwork for substantive legislative and administrative reforms. Read more about BGA and their executive director, Jay E. Stewart.

Charles N. Davis is former executive director of the National Freedom of Information Coalition and is an associate professor at the Missouri School of Journalism.